Pass By Value And Pass By Reference

Sometimes in programming, things don`t work the way you think they should. This can be frustrating.

However, as tempting as it is (especially when one is relatively inexperienced) to suspect your computer of playing up, this basically never happens.

Take the below example

#include <iostream>

void increase(int a, int b) {

a += b;

}

int main() {

int a = 2;

int b = 5;

increase(a, b);

std::cout << "The value of a is " << a << std::endl;

return 0;

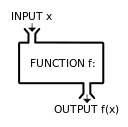

}Functions are so fundamental in programming that any nuances must be firmly grasped before moving on. We might expect the output to be

The value of a is 7

when in fact it is

The value of a is 2

a and b in increase are unrelated to a and b in main; what`s happening is something called pass by value.

In many languages (C++ and Java included), functions with primitive arguments (integers, floats, characters, booleans, etc.) pass their arguments by value. This means when the function is called, it copies its arguments.

When called, increase creates two local variables, a and b in a part of the computer’s memory called the stack.

However, because a and b in main are supplied as arguments to increase, a (b) on the stack is assigned the value of a (b) in main.

increase then does its work, leaving a on the stack with a value of 7.

Once all the lines in its body have been executed, its work is done. The stack is popped, i.e. everthing on it relating to increase is cleared from memory, and is no longer accessible in the program.

At no point have a and b in main changed.

How can we get our expected output? We could use pass by reference.

In C++, this can be done in two ways. We can add & to the function’s definiton like so

void increase(int& a, int b) {

a += b;

}Now, instead of creating a new variable a on the stack, the variable entered as the first argument is simply given a second name, a (here it is a bit silly as both names are a).

When increase modifies the value of a, it is modifying the actual variable that was entered as the first argument.

The second method is to use something called a pointer.

A pointer is a variable whose value is the address of another variable (every variable you declare has an address, i.e. a number corresponding to a location in the computer’s memory).

#include <iostream>

void increase(int *a, int b) {

*a += b;

}

int main() {

int a = 2;

int b = 5;

increase(&a, b);

std::cout << "The value of a is " << a << std::endl;

return 0;

}The above shows two usages of the asterisk symbol. In the first line of the function definition,

int *ameans a is a variable of type

int *i.e. the value of a is the address of another variable whose value is an integer.

In the second line,

*a += b;the asterisk symbol is used to say to the computer

I know

apoints to an integer. What I want is not the value ofa(an address), but the value of the integer that it points to.

This is known as dereferencing the pointer. increase takes this value and increases it by b.

When we call increase in main, the first argument is the address of a, written as

&aand the value of a is increased to 7.

Can we use these two methods in any language or are they specific to C++?

In C, we can only use the second method.

In Java, we can use neither as Java does not allow direct access to the computer’s memory. The closest solution in Java is to use a class variable via the keyword static:

import java.util.*;

public class Example {

public static int a = 2;

public static void increase(int b) {

Example.a += b;

}

public static void main(String[] arg) {

increase(5);

System.out.println("The value of a is " + a);

}

}In the last line we could also have written

Example.a instead of

a Doing so is longer but makes more explicit that a is a class variable rather than a regular attribute.

However, this kind of thing is frowned upon as class variables were not made part of the language to do things like the above.

Java, unlike C++, is designed to accommodate only a single paradigm, that of object-oriented programming. To better respect this paradigm, one should either make increase return 7:

import java.util.*;

public class Example {

public static int increase(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

public static void main(String[] arg) {

System.out.println("The value of a is " + increase(2, 5));

}

}or make use of objects.

This is because in Java, functions with object arguments pass them by reference.

Take the example of arrays, which in Java are considered as objects. If a function has an array as an argument and alters its value, the modification is permanent and is reflected in the rest of the program.

One of the advantages of pass by reference is that computing time and space are not wasted by pointless copying of variables.

If the variable is of a primitive type then this is not an issue. However, if it is, for example, a large array then copying that array can be costly. This is something I discovered when writing Java and C++ solutions to Problem 29 of Project Euler.

The Java solution took around 2 seconds whereas in C++ the implementation of the same solution did not return anything after a minute.

However, once functions had been changed to pass by reference, a solution was returned after 8 seconds (although given that C++ is supposed to be faster than Java, these extra 6 seconds are something of a mystery to me).